The Blue-Green Carpet & the fascinating bio-history of Oxygen on Earth

- sherjinjoel

- Sep 21, 2025

- 14 min read

Updated: Sep 22, 2025

Joel Sherjin

My workplace has occasional topic discussion sessions, and recently, I was asked to speak on sustainability in procurement. It is often much more difficult to talk about your favorite subject because every aspect of the topic comes to you like a parent having to choose between siblings. After a long, indecisive contemplation, I settled on starting with the Paris Agreement and the NDC commitments for countries, followed by the implications expected for big firms in the coming days. Since the audience ranged from diverse backgrounds, I planned to start with the Big Bang origin of the universe, a minor departure from the numbers and macroeconomic charts we usually talk about. To explain the fundamentals of today’s carbon footprint, I attempted to cover the Great Oxygenation, the formation of life, and how, in the last 100 years, the atmospheric carbon balance has changed. The harmful CO₂ (Carbon dioxide) released from natural sources (oceans, respiration, decomposition) is largely balanced by photosynthesis of plants, algae, and microorganisms, which absorb CO₂ and release Oxygen. However, the excessive human emissions of CO₂ add a net surplus and have been accumulating in the atmosphere. This has resulted in global warming, which is currently at 1.6 degrees. The Paris Agreement is a near-universal treaty that targets keeping this within 2 degrees.

Right after the presentation, I received some curious messages about the cyanobacteria I had talked about, which concocted photosynthesis and converted Earth’s uninhabitable, toxic atmosphere into one that is livable and supports bountiful life. I knew then that I had to come back and write a tribute to this gentle, invisible giant that deserves much more attention than it is possibly getting now. So, this is the long-short story of the Cyanobacteria and Oxygen. So, hang on with me and imagine the famous song from the film Sholay, Yeh Dosti Hum Nahi Chodenge, with a Cyanobacteria riding the motorcycle and the Oxygen riding on the good old sidecar attached to it. The journey begins…

Cyanobacteria — The Blue-Green Carpet

The story of the cyanobacteria is one of mundane wonders. The Clark Kent who, in reality, is the powerful Superman, or even an occasional Bollywood angry hero who is unassuming in the first half but capable of sending villains flying as the movie climaxes. Cyanobacteria, though not the most common center of attention while talking environment or sustainability, are one such. They belong to the group of phytoplankton that are bluish green, common across freshwater systems and open oceans. They can also colonize into layers and, in cases of a bloom, can cover the entire surface of the water body with a thick bluish green layer. Though quite widespread across continents, they are often ignored and bothered only by an odd swamp buffalo cooling off at noon, or an occasional bullfrog using the green camouflage as a cover from its predators.

I, for one, had not imagined much good coming from these occasionally foul-smelling algal patches. Some of my first troubles with them in my childhood days were that it made my guppy fish tank opaque frequently, which, in hindsight, really worked out for the guppies, who utilized the oxygen and nutrients from them and multiplied well without my frequent inspections and attempts to catch them. Just as the early life forms on Earth were nurtured by these Cyanobacteria.

In reality, they are one of the oldest life forms and are responsible for shaping the earth as we see it today. So, our hero for the day does not wear a cape exactly, but a blue-green carpet, and lives on the fringes unnoticed.

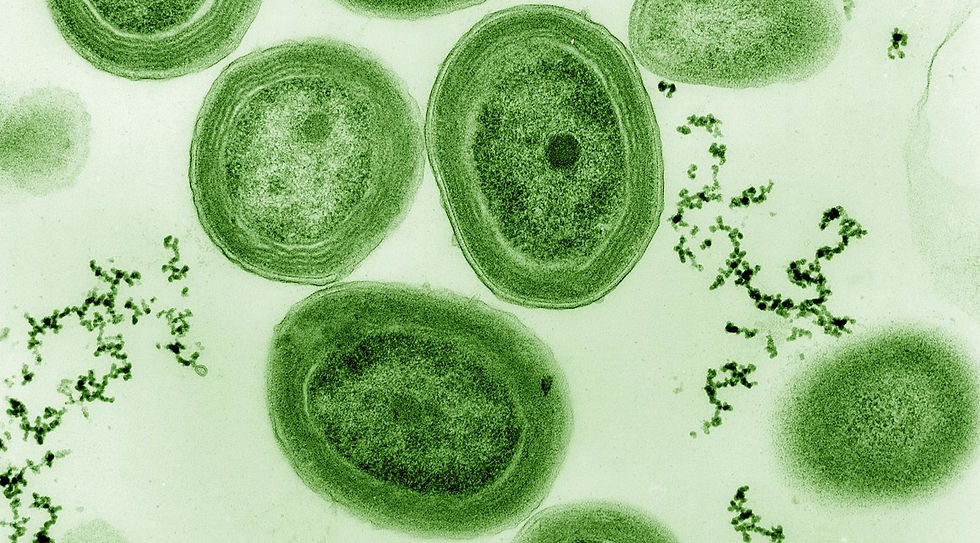

So, biologically speaking, what is a cyanobacterium?

Cyanobacteria are microscopic, single-celled organisms. They have a single cell with some pigments (Chlorophyll) and free-floating DNA, and were the sole producers of oxygen during the origin phase of life forms for over 3 billion years, while they spread all over the Earth and dominated it. I am still shy to use the word “habitats” here because the timeline we are talking about is 3.5 billion years ago, when Earth and life were at a very nascent stage, with Big Bang origin of the universe having happened about 1 billion years earlier. Earth was at best a giant earth-size reaction jar with high pressure, fire, acids, minerals, all dropped together and shaken vigorously. At this point, it wasn’t certainly the kind of planet aliens would look at through a Hubble and say, “Yes, there could be life possible there in that pale blue dot.”

Origin of Oxygen in the atmosphere

At some uncertain point, Cyanobacteria created photosynthesis, where their green pigments, especially chlorophyll, used sunlight to convert water and carbon dioxide into sugar, releasing oxygen as a waste product of the reaction.

6CO₂(Carbon Di Oxide) +6H₂O (Water) →C₆H₁₂O₆(Sugar)+6O₂(Oxygen)

This was a time when oxygen was a highly toxic chemical in the atmosphere. Other single-celled life forms were anaerobic; they did not know how to use oxygen, and in fact, oxygen often choked and killed them. For about 2 billion years since photosynthesis, cyanobacteria kept pumping oxygen into the atmosphere. But for a very long time, their work wasn’t appreciated or yielded much results, because every time they released oxygen, it quickly reacted with iron in seawater to form iron oxides that did not dissolve but sank to the bottom. These iron deposits are still visible today as valuable banded iron formations across the world.

Closer to home, Kudremukh is one such important Banded Iron Formation (BIF), created as a result of cyanobacteria releasing oxygen. Kudremukh (Western Ghats, Karnataka) is one of the largest deposits of banded magnetite quartzite, which is close to 3 billion years old. In the 1970s, the Indian government set up the Kudremukh Iron Ore Company Limited (KIOCL) to mine and export iron ore pellets, mostly to countries like China and Iran. But Kudremukh lies in a fragile high altitude grassland ecosystem of the Western Ghats, also a tiger reserve and watershed area where the river Bhadra originates. After years of protests and a Supreme Court case, mining was banned in 2005 to protect the ecosystem, and Kudremukh became a national park. There are such bands not too far, in Goa too.

Now, going back 2.5 billion years, once the oceans were devoid of free iron, and oxygen generated by Cyanobacteria often had no more abundant iron to react with. This resulted in excess oxygen finally being released into the atmosphere. This eventually caused the Great Oxidation Event, where an enormous amount of oxygen was released by billions of Cyanobacteria all around the Earth for a very long time, continuously changing Earth’s Chemistry. Oxygen poisoned many early microbes that couldn’t survive it, but eventually made Earth oxygen-rich.

Image 1: Banded Iron Formation: Copyright: By Graeme Churchard from Bristol, UK - Dales GorgeUploaded by PDTillman, CC BY 2.0,

Image 2: Kudremukh National Park. PC: Surya Ramachandran.

Rise of oxygen - Creating other life forms

While oxygen was becoming freely available, unicellular organisms were becoming aerobic (oxygen-breathing) and forming filaments, colonies, and sponges that were precursors to complex multicellular organisms. The most defining moment was around 1.5 billion years ago, when a larger unicellular organism swallowed a cyanobacterium. But, instead of digesting it, they lived together in a process called endosymbiosis, where they formed a mutually beneficial partnership. This became the first chloroplast, which is still more or less retaining its original form in all green plants. The evolution of chloroplasts birthed algae, plants, and forests, further spreading photosynthesis and releasing more oxygen into the atmosphere.

In the meantime, cyanobacteria glued to each other and started forming mats that trapped dust and sand. Eventually, they hardened into colonies in multiple shapes, like layered rocks and mounds. These are called stromatolites, which are among the earliest fossils to store historical information about the origin of life.

Oxygen: Creating the Ozone Barrier Layer for the Earth

Then the Earth cooled, and with oxygen rising, around 600 Mya (Million years ago), oxygen became so abundant and reached the top of Earth’s atmosphere. There, UV rays from the Sun bombarded and split O₂ molecules, and the free oxygen atoms recombined into ozone (O₃). Slowly, the ozone layer formed, blocking UV rays. This was a major shift and a gift for life forms: until then, life survived only in deep waters or sheltered places owing to harsh UV rays. With ozone shielding these harmful rays, algae and plants started colonizing the Earth’s surface, creating forests and large swamps across open lands.

The Oxygenation Event (600–541 Mya) – More Oxygen and more life

Multicellular beings now began to appear, which are Ediacaran biota - soft-bodied organisms shaped like fronds, discs, and tubes. Most of these went extinct in the subsequent millennia, leaving little trace for us to study. Then evolution shifted gears, powered by increasing oxygen from cyanobacteria, now additionally charged with photosynthesizing algae and large forests, which led to the Cambrian Explosion (~540 Mya). This is a watershed moment, when almost all major animal groups suddenly appeared in the sea, in some kind of rapid evolution, developing hard shells, skeletons, eyes, nerves, and mobility. Many were ancestors of today’s vertebrates.

The first true land animals (amphibians) appeared around 400 Mya. By now, land was colonized by algae, plants, and animals. Cyanobacteria, though omnipresent, were no longer the largest oxygen producers, as they were superseded by the terrestrial giant swamps and ferns, which are themselves descendants of Cyanobacteria that created chloroplasts.

Earth’s peak Oxygen Moment and the impact

Oxygen peaked in the Carboniferous–Permian (350–300 Mya) at ~35% of the atmosphere, which is the highest ever. Life exploded in size with steroid shots of excess oxygen. Giant dragonflies, huge amphibians, vast tropical wetlands, and giant trees and ferns started evolving across continents. (refer to my earlier piece on Giant Dragonflies here) This high concentration of O₂ in the atmosphere was due to limited or no decomposition of plant matter happening, where CO₂ would have been released into the atmosphere. While photosynthesis kept increasing, from exploding plant matter releasing Oxygen. In fact, at this point, Fungi and termites, which decompose and release CO₂ from dead plants and wood, have not even originated yet. The swamps, ferns, plants, and trees, when they die, were not eaten by termites and fungus, and were just getting buried deep and covered by layers of dust, silt, and other earth surface metamorphosis events. A big gift of this phase is the massive Coal reserves we now have, which we are mining and using to power human activities. These coal reserves are primarily the large dead swamps being buried before the arrival of decomposers for a very long time. For this reason, this period is called the Carboniferous era, which translates to Carbon/Coal Bearing time.

So, to add a bit more context, Large animals, Dinosaurs, and mammals have not yet evolved, as respiration of faunal life was still happening through tiny Tracheal tubes and not lungs, which can support large-bodied animals. This happened later in the Mesozoic period, after 240 Mya. But just before that, the unfortunate, inevitable event in the life of Earth had to happen.

Oxygen's big decline & the Great Dying: ~ 250 million years ago

Later, Oxygen fell drastically to ~15% during the Permian decline, leading to the Great Dying. The massive volcanic eruption in the Siberian Traps went on for about a million years and filled the atmosphere with CH₄ (methane) and CO₂ (carbon dioxide). Fire raged everywhere with acid rains and toxins filling the earth and oceans. The carefully built ozone layer was also possibly damaged, and with the added greenhouse effect, global warming went up by 5 – 10 °C. Ocean acidification further severed waterborne food webs, resulting in catastrophic mass deaths. Out in the lands, the evolution of lignin processing fungi (white-rot basidiomycetes) and its rapid spread across the land started decomposing large masses of trees and plant masses that have died over millions of years, and also the ones that are currently dying, resulting in enormous volumes of CO₂ being released into the atmosphere. Heat and drought ravaged across the Earth, and as a result, 80 - 90% of marine species and about 70% of terrestrial vertebrates died, rendering the Earth almost lifeless.

It all had to start all over again. Plant life eventually recovered, forests spread, and oxygen rose back to ~23–25% in the next 10 million years. Cyanobacteria, meanwhile, adapted to survive. Stromatolites, their hardened colony forms, declined, but they survived everywhere, with some of them still alive in Australia and Mexico. Cyanobacteria had to become more innovative and began experimenting with partnerships. Now with fungi becoming abundant, they formed partnerships, becoming a hardened form - the lichens, which are so widespread now across habitats, playing a major part in air fixation and also making soil by eroding rocks even in inhospitable places on earth. They also experimented with living inside corals and Sponges and were successful. They further developed their technique to process Nitrogen in the atmosphere and entered into symbiotic ‘situationships’ with cycads, Ferns, and mosses, living in their roots and helping in nutrients by nitrogen fixation, which they still successfully do.

The Age of Giant Dinosaurs – Lungs adding more Oxygen to animal life

By ~200–150 Mya, dinosaurs evolved and dominated. Large mammals, which looked very different from those today, also evolved and spread across landscapes on Earth's surface. Novel ways of Respiration through large sacks called 'Lungs' helped animals absorb more Oxygen, helping them grow in gigantic proportions. The Argentinosaurus is the largest of them, estimated to have grown to 40 meters long, weighing about 100 tons, which is about 25 large Asian Elephants. Much closer to home, in 1980, the village of Kallamedu in Tamil Nadu made it to the Bio-Paleo world stage with the excavation of a giant dinosaur (Titanosaurus) that could have weighed about 170 tons, named as Bruhathkayosaurus – meaning giant lizard in Sanskrit. However, this finding could not be strongly established as the very fragile fossil disintegrated before further studies. This is still a testimony to how Oxygen was transforming the scale of life forms and handholding evolution in various trajectories.

There were still volcanic activities going on, and the continents’ surface kept rearranging like a puzzle being solved. Present Chennai and most of the Eastern coast of India shared a boundary with Antarctica during this time, while they were sutured together as the continent of Gondwana. They eventually started breaking up and drifting apart around 130 Mya (Million years ago).

Around 66 Mya, an asteroid hit the Earth near the Gulf of Mexico, and repeated volcanism wiped the Dinosaurs and most large mammals out. Oxygen still remained fairly stable through these events.

Arrival of Humans and their tryst with Oxygen

By 2.5 Mya, oxygen was ~21%, about the same as today, coinciding with the appearance of early humans in Africa. Homo sapiens arrived much later, around ~300,000 years ago. Oxygen or CO₂ levels did not shift much even through the following ice ages.

But the atmospheric composition started changing rapidly with human activity in the last 200 years, largely by releasing alarmingly excess of CO₂ through burning fossil fuels and mining activities. CO₂ levels have risen by roughly 50% in just 100 years and are severely affecting the fragile balance maintained in the atmosphere after millions of years of stability even throughout geologic events of massive scale. Oxygen, though still abundant, met with a minor decline of about 0.03% - not a threat as yet.

Cyanobacteria now - Are they still relevant?

Almost100% of the present Earth’s oxygen can be traced back to cyanobacteria and their descendants (chloroplasts). Today, 60–70% of oxygen is still generated in oceans, of which Cyanobacteria contribute to over half. Oxygen's nurture of human life cannot be understated. An average human uses about 700 liters of oxygen every day. Every year, we consume equivalent oxygen from 3 mature trees a year, or the cyanobacterial productivity of hundreds of millions of liters of seawater. An easier way of replenishing the oxygen we consume could be by planting 3 trees a year, certainly easier than generating millions of liters of active seawater. A reductive fallacy? Yes, this is an oversimplification of the complex balance sheet of O2 consumption and release. But only my attempt to gently coax more shade and birdsongs to our scorching neighborhoods.

Cyanobacteria are present everywhere, even now: oceans, rivers, ponds, rocks, polar ice, and even inside other organisms, including us. In oceans, the dominant ones are Prochlorococcus and Synechococcus, which can number in the millions per glass of any seawater. Across all Inland freshwaters, larger filamentous forms like Anabaena and Microcystis are common. Excess blooms, where the waterbody can get covered in a thick green layer, are a rising concern: cyanobacteria are not officially listed as harmful contaminants yet, but many studies highlight their risks when ingested in high concentrations. Human effects and pollution are causing frequent occurrences of these blooms and eventual eutrophication (a decomposition that strips O₂), causing mass deaths of water life. A closer example of these blue-green blooms is the frequent blooms in Bellandur and Varthur lakes of Bangalore, which often make it to the news for not the best reasons.

Meanwhile, Oxygen: The Elixir of Life, also, is a weapon to Destroy Life!

Humans discovered fire - combustion of oxygen with cellulose releasing CO₂, and energy in the form of fire and heat, which changed our course forever. This newfound use of oxygen powered the entire industrial revolution, using the very same Coal cyanobacterium that helped accumulate. They are enabling everything from stoves to rockets. This, in turn, has been increasing harmful CO₂ emissions, sending us on a path of self-destruction of life on the planet.

Our tryst with oxygen became most emphasized in the last five years: COVID-19 made oxygen availability a headline every day, imprinting, in a rather painful way, Oxygen’s importance of sustaining life in our collective memory. Personally, my tryst with oxygen comes every time I go to the Himalayas, where altitude sickness makes me surrender to its undeniable power through near-death experiences that I should have clearly avoided. As air pressure drops, oxygen intake through respiration falls by ~10% every 1,000 meters, and above 4,000m, only ~60% of sea-level oxygen is available. Our human brain, using 20% of our oxygen intake, struggles with the low fuel alters, and sometimes it can be fatal. Watching a snow leopard in Ladakh or looking for a red panda in Sandakphu, I’ve felt sliding towards cerebral edema before rushing downhill for medical help. Since then, I have been limiting my travels to seeing high hills only from a safe distance of abundant oxygen.

The journey of Mundane to Wonder - Cyanobacterium

A relatively not-so-serious encounter was when my friend let go of me while I leaned over a puddle in the Eastern Himalayas to look at a lifer, a Himalayan newt, splashing my face with a mat of Cyanobacterial bloom. In that moment, many years ago, certainly disgust outweighed wonder. That blue-green carpet is the oldest life form on Earth and is still creating, nurturing, expanding, and transforming life forms on Earth since its origin 3.5 billion years ago, without ever making a noise about its service. Like the beautiful story of symbiotic relationship in Sholay, the coin had heads on both sides - it was the Cyanobacteria all along, orchestrating the show. They are the quiet authors of Earth’s story. What I have learnt from them is never to take the mundane for granted. Majestic stories lie hidden mostly in the overlooked - the rocks, plants, and the dullest of insects. Trying to know them and deep dive into their stories, for me, is maybe a small step in appreciating what we have, like the Bluish Green Cape wearing - Cyanobacteria.

Science is a painful pursuit, the more you understand, the more you dont understand!

If you’ve made it this far, thank you for sticking with a long-form piece. If you have a moment, please scroll to the bottom of this page and share your thoughts. I’d be deeply grateful.

Notes & References

[1] Lyons, T. W., Reinhard, C. T., & Planavsky, N. J. (2014). The rise of oxygen in Earth’s early ocean and atmosphere. Nature. Also see: Donald E. Canfield, Oxygen: A Four Billion Year History (Princeton University Press).[2] Canfield, D. E. (2014). Oxygen: A Four Billion Year History; Holland, H. D. (2006). The oxygenation of the atmosphere and oceans. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B. (For Carboniferous peak ~30–35% O₂.)[3] Burgess, S. D., Bowring, S. A., & Shen, S.-Z. (2014). High-precision timeline for Earth’s most severe extinction. PNAS. (For end-Permian “Great Dying” and associated drivers.)

Additional sources / further reading

Pranay Lal, Indica: A Deep Natural History of the Indian Subcontinent (Penguin).

T. R. E. Southwood, The Story of Life (Oxford University Press).

Prosanta Chakrabarty, Explaining Life Through Evolution (MIT Press).

Andrew H. Knoll, Life on a Young Planet (Princeton University Press).

R. E. Ernst, Large Igneous Provinces (Cambridge University Press).

Geological Survey of India reports on Banded Iron Formations (Kudremukh, Goa belts).

Fascinating article. I never imagined a single celled cyanobacterium would be responsible for the evolution of earth and bringing life on earth. Really must not take mundane things for granted.

Hi Joel,

Thank you for this insightful information.

It took me to the timelines of each events!

Thanks for this.